Katherine Moore spends her days surrounded by bones. On the lower floor of the Penn Museum, down an elevator beside the café and through two locked doors, her lab’s shelves are stacked with the skeletal remains of everything from llamas and cattle to pigs, fish, and guinea pigs.

This isn’t just any cabinet of curiosities: It’s the Center for the Analysis of Archaeological Materials (CAAM), and its osteological library is a key tool in Moore’s mission to unpack our historical eating habits.

“Look at that rough break,” she says, holding up a cow’s tibia from the 18th century. “That shows that this animal has been butchered and prepared for meat in a very informal, non-market-based way.” She notes that bones from later centuries often sport cleaner cuts, showing that the meat was sawn carefully to be sold at a market.

Moore, a zooarchaeologist, knows that most people come to the Penn Museum for what lies above her lab: showstoppers like the 13-ton granite sphinx and Queen Puabi's golden headdress. Displays of her food-focused specimens of bones and meat, in contrast, sometimes have visitors scratching their heads.

“People sometimes come to an archaeological museum thinking it's going to all be art,” Moore says. “And then there's chunks of dried meat lying there and they wonder, ‘What? Where am I now?’”

But with its new Ancient Food & Flavor exhibit, the Penn Museum's thousand-year-old llama jerky and apples older than Stonehenge are getting their turn in the spotlight. The exhibit focuses on culinary artifacts from three sites: Robenhausen, a 6,000-year-old village in Switzerland; Numayra, a 4,500-year-old community in Jordan; and Pachacámac, an 1,800-year-old city in Peru.

All the artifacts—which range from freeze-dried potatoes and grinding stones to fish scales and livestock dung—offer clues about ancient diets and lifestyles. Moore, who co-curated the exhibit, points to an animated video that imagines a robust trade hub in Pachacámac, one of three videos playing throughout the exhibit (the others depict a farm at Robenhausen and winemaking at Numayra). A comprehensive portrait like this, she says, is the result of years spent analyzing the small pieces of information offered by these specimens.

“Every motion, every animal, every plant” featured in the video, she explains, is based on archaeological findings like those showcased in the exhibit.

The animated depiction of Pachacámac shows llamas loaded up with provisions—a concept drawn from the weathered transport pouches, dried meat, and remarkably preserved corn, chiles, and potatoes in the glass cases around the video display. “They were in a large, politically integrated area that stretched over about two-thirds of South America,” Moore explains. “And so the picture we chose . . . is the trade: food from the sea, food from local environments.”

By displaying the artifacts alongside the animated depictions of daily life, the exhibit provides a glimpse not just into early eating habits, but also how scientists like Moore and her co-curator, Chantel White, use ancient plants, pottery, and bones to decipher the mysteries of food history. Since it’s rare to excavate complete meals, studying ancient cooking and cultivation requires some archaeological detective work.

“We don't just want to pluck little single objects out,” says White, an archaeobotanist. “It's also about the context of where they're found.”

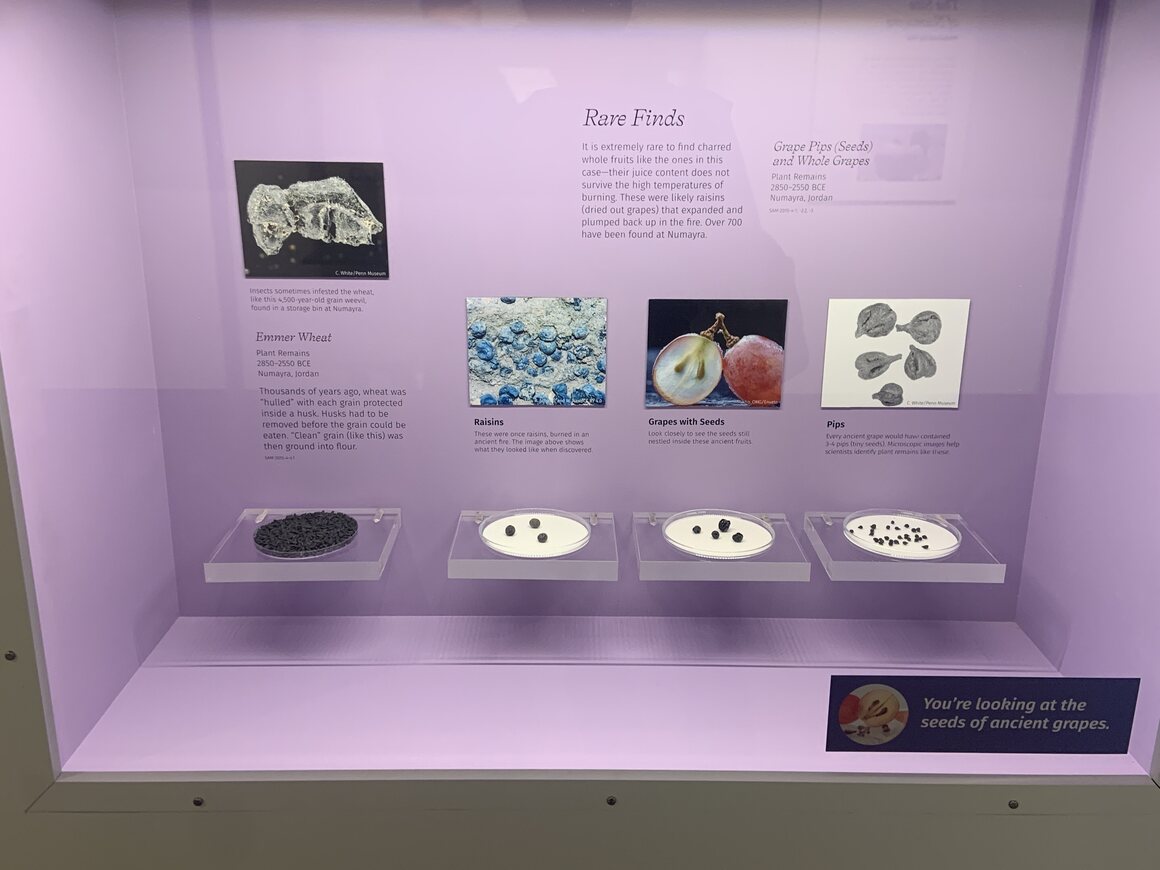

For White, studying the plant matter from a room at Numayra—which was destroyed by a fire sometime between 2850 and 2550 BCE—was a passion project. When archaeologists excavated the site in the late 1970s and early ’80s, they found shattered pots, carbonized grapes, and thousands of tiny grape seeds both in the pots and scattered across the floor.

“Initially I was like, ‘Why in the world would there be so many grape seeds?’ But it makes sense when you think about if this was part of the grape fermentation process,” White explains. “All these grape seeds would have been at the bottom of the vessels.”

White also notes that the grapes showed signs of having been stomped. The exhibit encourages visitors to look for similar visual evidence, providing microscopes and magnifying glasses to identify possible signs of grinding, fermenting, or cooking on the seeds and fish scales excavated from the sites.

But when the powers of observation fail to provide answers, it’s time for a more hands-on approach.

“We have a little slogan in CAAM,” Moore says. “It’s called ‘Let’s try it!’” Sometimes “trying it” might mean smashing nuts with a palm-size stone to match the marks made on cracked hazelnuts found at Robenhausen. (“I have a slab of stone and a handstone that are greasy, at this point, because I've done this so many times,” Moore says.) Other times, that might mean burning crabapples inside the furnace in White’s lab to mimic the charring on 6,000-year-old carbonized fruit. And sometimes, it means conducting tests in your own backyard: “Once, someone called the police on me when I was trying to do a relatively extensive controlled burn,” Moore laughs.

No matter the approach, the goal is always to reconstruct the archaeological findings and better understand how early humans cultivated, prepared, or preserved their food.

Moore and White are even conducting an experiment within the exhibit: In an outdoor courtyard, several plots grow the same plants displayed inside. Organized by country, the gardens contain crops from Jordan (chickpeas, flax), Peru (corn, quinoa, chiles), and Switzerland (rye, hazelnuts, strawberries). Moore points out that the garden has already made her feel connected with some of her ancestors’ struggles—especially when it comes to coping with pests.

“We really asked for it, having our exhibit outside,” she laughs. “The squirrels already got to the corn.”

But even pests can provide an education in food history. Beyond the exhibit, Moore and White are currently studying rats’ nests from enslaved workers’ quarters in South Carolina from 1830 to 1860. The rodents’ stashes of stolen food and gnawed materials can offer new insights into how their human neighbors lived.

Like antebellum rats’ nests, the Ancient Food & Flavor exhibit shows the value behind an overlooked aspect of history. Dried apples and tiny ancient grape seeds may not be as flashy as royal jewelry or mummies, but, Moore says, they’re no less important.

“We are not here to talk about golden headdresses,” she says. “We are here to talk about the lives of people in the past who did this work, who produced this food, who kept everybody alive, and who labored on their hands and knees. This is the labor of your ancestors. No one alive today isn't descended from someone who had to do this work by hand.”