[ comments ]

Key Findings

- The Citizen Lab, in collaboration with Catalan civil society groups, has identified at least 65 individuals targeted or infected with mercenary spyware.

- At least 63 were targeted or infected with Pegasus, and four others with Candiru. At least two were targeted or infected with both.

- Victims included Members of the European Parliament, Catalan Presidents, legislators, jurists, and members of civil society organisations. Family members were also infected in some cases.

- We identified evidence of HOMAGE, a previously-undisclosed iOS zero-click vulnerability used by NSO Group that was effective against some versions prior to 13.2.

- The Citizen Lab is not conclusively attributing the operations to a specific entity, but strong circumstantial evidence suggests a nexus with Spanish authorities.

- We shared a selection of Pegasus cases with Amnesty International’s Tech Lab, which independently validated our forensic methodology.

Click here for a graphical overview of our findings.

Introduction

In 2019, WhatsApp patched CVE-2019-3568, a vulnerability exploited by NSO Group to hack Android phones around the world with Pegasus. At the same time, WhatsApp notified 1,400 users who had been targeted with the exploit. Among the targets were multiple members of civil society and political figures in Catalonia, Spain. The Citizen Lab assisted WhatsApp in notifying civil society victims and helping them take steps to be more secure.

The cases were first reported by The Guardian in 2020. Following these reports, the Citizen Lab, in collaboration with civil society organisations, undertook a large-scale investigation into Pegasus hacking in Spain. The investigation has uncovered at least 65 individuals targeted or infected with Pegasus or spyware from Candiru, another mercenary hacking company.

Forensic evidence was obtained from victims who consented to participate in a research study with the Citizen Lab. Further, victims publicly named in this report consented to be identified as such, while other targets chose to remain anonymous. Confirmed cases of Pegasus and Candiru hacking (i.e. when the spyware is successfully installed on a device) are referred to as “infections” or being “infected” throughout the report, while “targeted” refers to an act of targeting with Pegasus or Candiru spyware that may or may not correspond to a forensically-discovered infection (i.e. because a device was unavailable for analysis, or is an Android which is more difficult to forensically analyse). “Hacking” is used as a global term to describe the act of targeting and/or infecting devices.

The hacking covers a spectrum of civil society in Catalonia, from academics and activists to non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Catalonia’s government and elected officials were also extensively targeted, from the highest levels of Catalan government to Members of the European Parliament, legislators, and their staff and family members. We do not conclusively attribute the targeting to a specific government, but extensive circumstantial evidence points to the Spanish government.

Background: Spain, Catalonia, and Surveillance

Following three years of civil war spanning from 1936 to 1939, and thirty-six years of brutal dictatorship under General Francisco Franco, Spain’s government transitioned into a democratic, constitutional monarchy in 1975-1978. Under the King as head of state, Spain’s elected Prime Minister and Council of Ministers form the government. The Spanish Parliament appoints, and dismisses, the prime minister. Pedro Sánchez, leader of the Socialist Workers’ Party, currently serves as prime minister, a position he has held since 2018.

Spain maintains a robust security and intelligence apparatus largely as a function of the country’s experience with terrorism and organised crime. The National Intelligence Center (CNI) acts as both a domestic and international intelligence agency, while the Guardia Civil is the country’s policing and law enforcement body of a “military nature.” Both are accountable to the head of government through the Ministry of the Defense. As with most countries’ intelligence agencies, the CNI’s activities are shrouded in secrecy, and the agency lacks public transparency. The CNI has also been at the centre of a series of surveillance and espionage scandals. Ensuring transparency and public accountability in the operations of Spain’s intelligence apparatus is an enduring challenge, despite the requirement of some judicial oversight.

Background on Catalonia’s History and Government

The autonomous community of Catalonia (one of several autonomous communities in Spain) is located in north-eastern Spain and comprises four provinces: Girona, Barcelona, Tarragona, and Lleida. Catalonia is considered among the wealthiest regions of Spain and its economy represents a significant portion of Spain’s Gross Domestic Product. The region’s official languages are Catalan and Spanish. Catalonia has a long and complex history and its desire for greater autonomy and independence has roots that date back hundreds of years. Catalonia’s autonomous status, culture, and society were persecuted throughout Franco’s dictatorship, until it regained autonomy following the regime’s demise in 1977-1978. Since Catalonia’s 1979 Statute of Autonomy, efforts in favour of greater autonomy ebbed and flowed for several decades, but grew larger and more organised leading up to the 2003 elections. The winning coalition led by Pasqual Maragall produced the 2006 Statute of Autonomy. Maragall said the Statute would grant Catalonia unprecedented, “state-like” autonomy.

Events Leading Up to and Following the 2017 Referendum

The campaign for a fully independent Catalonia, while divisive, gradually gained traction in the late 1990s. The momentum then accelerated following the 2008 financial crisis. In 2009, the municipality of Arenys de Munt held a referendum on the secession question (96% in favour, 41% turnout). Self-determination referenda have been found to violate Article 2 of the 1978 Spanish Constitution, which entrenches the “indissoluble unity” of the nation. Notwithstanding, Arenys inspired other Catalan municipalities to hold similar referenda. Over the next year and a half, 58.3% of Catalan municipalities—constituting 77.5% of Catalonia’s population—held separate referenda.

In 2010, Spain’s Constitutional Court struck down certain sections of the 2006 Statute of Autonomy, which governs the relationship between Catalonia and Spain. This decision led to a massive protest in Barcelona. Further, significant pro-independence protests (accompanied by the slogan “Catalonia, a new European state”) followed in Barcelona in 2012. On the heels of the protest, the Catalan government issued a resolution affirming “a new era based on the right to decide.” This resolution, and others, were systematically rejected by the Spanish Constitutional Court. In 2014, after an attempt to hold an official referendum was ruled to be illegal by the Constitutional Court, the Catalan government held a non-binding self-determination referendum, also referred to as the Citizen Participation Process on the Political Future of Catalonia. The referendum led to serious consequences for the then president of Catalonia, Artur Mas, and some other government officials.

In 2017, Carles Puigdemont—the successor to Mas—announced before the Catalan Parliament that he would hold a binding referendum on independence. The referendum was held on October 1, 2017, despite Spain’s Constitutional Court finding the referendum to be illegal under Spanish law. Of those who voted, 90% supported independence, although the final turnout was low at only 42% of voters. At the time, the Catalan government’s spokesperson stated that the count did not include ballots seized in raids by the Spanish police. There were also reports of police turning away voters from polling places. During the referendum, Human Rights Watch described the Spanish police as using excessive force when confronting peaceful demonstrators. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, called for an independent investigation into the violence, and urged that the dispute be resolved through dialogue.

In late October 2017, the Catalan Parliament approved a resolution in favour of independence, with 72 of the 135 members signing. The Spanish government responded by firing Puigdemont, dissolving the Catalan Parliament, and scheduling new elections. Regardless, pro-independence parties still won a majority in the new Parliament. Puigdemont, meanwhile, had fled Catalonia, accompanied by several colleagues. Although some later returned to face trial, Puigdemont remained in Brussels. He was subsequently elected as a member of the European Parliament, and continues to fight extradition to Spain.

Reportedly, the CNI collaborated with German intelligence agencies to undertake surveillance on Puigdemont leading to his March 25, 2018 arrest in Germany. In October 2019, the Supreme Court of Spain sentenced a number of Catalans convicted of sedition for participating in the 2017 referendum to prison terms of nine to 13 years. Several international human rights organisations strongly criticised the convictions and sentencing as potential violations of international human rights law. The sentencing sparked new protests, including calls for non-violent civil disobedience organised by a tech-savvy independence movement called the Tsunami Democràtic. The Catalans convicted of sedition were eventually pardoned by the Spanish government in 2021.

Spanish courts have determined that Catalan secession is contrary to Spanish domestic and constitutional law. But the question may be more nuanced under international law and raises legal questions related to territorial integrity, self-determination, declarations of independence, secession, and recognition. Negotiations between Catalonia and the Spanish government resumed in September 2021, after a hiatus of a year and a half. In February 2022, Pere Aragonès—now president of the government of Catalonia – indicated that he was open to continuing negotiations with the Spanish government.

Documented Surveillance Abuses in Spain and Catalonia

While secrecy surrounds Spain’s surveillance practices, a number of cases have come to light over the last several decades that are relevant to this report and demonstrate a track record of domestic surveillance and the use of spyware by Spanish authorities. In 2001, Mariano Rajoy, then Spain’s Minister of Interior, purchased the Sistema integral de interpretación de las comunicaciones (SITEL), spyware the Guardia Civil and CNI used to track suspects’ phones. Spain also reportedly ‘colluded’ with the National Security Agency (NSA) in the United States. The 2013 Snowden disclosures revealed that the NSA had intercepted 60 million calls in Spain between December 2012 and January 2013.

According to el Confidencial, the CNI and National Police paid at least 209,000 euros to the Milan-based surveillance software company Hacking Team for use of its spyware in 2010. The purchase was first revealed in 2015 when WikiLeaks published internal Hacking Team emails. El País then reported that the contract with the CNI was “valid from 2010 to 2016, worth 3.4 million euros.” The CNI acknowledged it purchased the spyware at the time, saying it did so “in accordance with the public sector contracting laws.” CNI declined to give any further information as to what they did with Hacking Team’s spyware. In 2015, the Citizen Lab mapped the proliferation of Finfisher, a sophisticated computer spyware suite sold exclusively to governments for intelligence and law enforcement purposes, and identified a suspected Spanish customer.

The latest targeted espionage scandal in Spain arose publicly in 2020 when several prominent Catalans announced that WhatsApp and the Citizen Lab had notified them that they were targeted in the 2019 WhatsApp Pegasus breach. The first to do so was Roger Torrent, then pro-independence president of the Catalan Parliament. The targeting of Torrent with NSO Group’s spyware was confirmed by WhatsApp. Ernest Maragall, leader of the pro-independence, Barcelona-based Republican Left of Catalonia party, was the second target to come forward, followed by Anna Gabriel, a former regional member of Parliament for the far-left party, the Popular Unity Candidacy (CUP), activist Jordi Domingo, and Puigdemont staffer Sergi Miquel Gutiérrez. Gabriel was targeted while she was living in Switzerland. The Spanish prime minister’s office claimed that it was “not aware” of this spying. Nonetheless, in 2020, El País confirmed that the Spanish government was an NSO Group customer, and that the CNI actively used Pegasus spyware. A former NSO employee commented to Motherboard that they “‘were actually very proud of them as a customer’ … ‘Finally, a European state.’”

Finding: Catalans Targeted with Pegasus

With the targets’ consent, we obtained forensic artefacts from their devices that we examined for evidence of Pegasus infections. Our forensic analysis enables us to conclude with high confidence that, of the 63 people targeted with Pegasus, at least 51 individuals were infected.

Almost all of the incidents occurred between 2017 and 2020, although we found an instance of targeting in 2015. All targets publicly named in this report consented to be identified as such.

In addition to the forensic confirmations, we identified additional cases of Catalans targeted by Pegasus infection attempts, but where we were unable to forensically validate an infection. This was due to multiple reasons, ranging from changed or discarded devices, to the limitations of our forensic tooling.

| Case Type | Number observed |

|---|---|

| Individuals with forensically-confirmed infections. | 51 |

| Individuals targeted via SMS or WhatsApp with Pegasus infection attempts, without forensic confirmation of a successful infection. | 12 |

| Total Pegasus targets | 63 |

Table 1: Pegasus Infection and Targeting Overview

Spain has a high Android prevalence over iOS (~80% Android in 2021). Anecdotally, this is somewhat reflected in the individuals we contacted. Because our forensic tools for detecting Pegasus are much more developed for iOS devices, we believe that this report heavily undercounts the number of individuals likely targeted and infected with Pegasus because they had Android devices.

Relational or “Off-Centre” Targeting

Targeting friends, family members, and close associates is a common practice for some hacking operations. This technique allows an attacker to gather information about a primary target without necessarily maintaining access to that person’s device. In some cases, the primary target may also be infected, but in others this may not be feasible for various reasons.

We observed several cases of relational or “off-centre” targeting: spouses, siblings, parents, staff, or close associates of primary targets were targeted and infected with Pegasus. In some cases those individuals may also have been targeted, but forensic information was unavailable. In others, we found no evidence that a primary target was infected with Pegasus, but found targeting of their intimates.

For example, one individual targeted with Candiru had a US SIM card in their device, and resided in the US. We failed to find evidence that this individual was infected with Pegasus. This is consistent with reports that most Pegasus customers are not permitted to target US numbers. However, both of the target’s parents use phones with Spanish numbers, and were targeted on the day that the primary target flew back to Spain from the US. Neither parent is politically active or likely to have been targeted because of who they are or what they do.

Target: Members of the European Parliament

Every Catalan Member of the European Parliament (MEP) that supported independence was targeted either directly with Pegasus, or via suspected relational targeting. Three MEPs were directly infected, two more had staff, family members, or close associates targeted with Pegasus.

Diana Riba (MEP, ERC), who assumed office in July 2019 was infected on or around October 28, 2019. Antoni Comín (MEP, JUNTS), who also assumed office in July 2019, was infected sometime between August 2019 and January 2020. He had assumed his role as a MEP in July 2019. Antoni Comín is also Vice President of the Council of the Catalan Republic.

In some cases, the targeting coincided with political events, underlining that the targeting may have been for the purposes of political espionage. For example, Jordi Solé (MEP, ERC) was targeted during party discussions about who would replace MEP Oriol Junqueras. One instance took the form of a fake SMS from Spain’s social security system. Forensic evidence confirms that he was infected at least twice on or around June 11 and June 27, 2020, shortly before being substituted into his role as a MEP in July 2020.

These dates and findings do not preclude the possibility of other infections or targeting. As with other victim clusters, we were not always able to fully forensically examine all relevant devices.

Direct Targeting

-

Antoni Comín Infected (Pegasus)

- Member of the European Parliament, JUNTS ( 2019 – present)

- Former Minister of Health of Catalonia (2016 – 2017)

-

Diana Riba Infected (Pegasus)

- Member of the European Parliament, ERC (2019 – present)

-

Jordi Solé Infected (Pegasus)

- Member of the European Parliament, ERC (2020 – present)

- Former Member of the Parliament of Catalonia (2012 – 2015)

- Infected during discussions leading to his substitution into the role of a previous MEP.

Likely Relational Targeting

-

Clara Ponsati Relational targeting against a European Parliament staff member

- Member of the European Parliament, JUNTS (2020 – present)

- Former Minister of Education of Catalonia (2017 – 2017)

-

Carles Puigdemont Relational targeting via key staff, spouse, and close associates

- Member of the European Parliament, JUNTS (2019 – present)

- Former President of Catalonia (2016 – 2017)

We observed Pol Cruz, a key parliamentary staff member of Clara Ponsati (MEP, JUNTS), infected with Pegasus on or around July 7, 2020.

The spouse, key staff members, and close associates of Carles Puigdemont (MEP, JUNTS) were all targeted with Pegasus. We count up to eleven individuals that fit this category. For example, Marcela Topor, his spouse, was infected at least twice (on or around October 7, 2019 and July 4, 2020).

Target: Catalan Civil Society

Multiple Catalan civil society organisations that support Catalan political independence targeted with Pegasus, including Òmnium Cultural and Assemblea Nacional Catalana (ANC). Catalans working in the open-source and digital voting communities were also targeted. This section highlights a selection of the cases.

Target: Assemblea Nacional Catalana (ANC)

At ANC, five board members were targeted, including university professor Jordi Sànchez (President, 2015 – 2017). Interestingly, Sànchez was first seen targeted with a Pegasus SMS infection attempt via SMS 2015, shortly after a large demonstration in Barcelona. This is the earliest Pegasus infection attempt that we have observed as bulk of the targeting uncovered by this investigation appears to have occurred between 2017 and 2020.

| Organization | Number of targets |

|---|---|

| Òmnium Cultural | 4 |

| ANC | 5 |

Table 2: Targeted Catalan organizations

Between 2017 and 2020, Sànchez received at least 25 more Pegasus SMSes, most of which masqueraded as news updates relating to Catalan and Spanish politics. He also received messages purporting to come from the Spanish tax and social security authorities.

Messages received by Sànchez often coincided with important political events. For example, on April 20, 2017, he was targeted the day prior to Catalan government meetings with civil society groups to discuss the October referendum. Months later, just as polling stations opened on October 1, 2017, he was targeted with an alarming message saying that a police “offensive” was beginning. Forensic analysis confirms that Sànchez was infected at least four times with Pegasus between May and October 2017.

Sanchez is among the prominent Catalans arrested, and later pardoned, for their role in the Referendum. One of the infections occurred on October 13, 2017, just days before his arrest. Interestingly, the SMSes targeting his phone in 2020 coincided with days when he was given weekend release from jail.

Professor Elisenda Paluzie (ANC President, 2018 – 2022) is a prominent Catalan economist, academic, and activist. Prior to her role with the ANC, she served as dean of the Faculty of Economics and Business at the University of Barcelona.

She was working from home during the COVID lockdown when the first Pegasus infection attempt arrived. It purported to be a news story about the ANC. On June 10, 2020, as she was running for a board seat with ANC and as online voting began, a second infection attempt arrived. It masqueraded as a Twitter update from a Catalan newspaper.

Another ANC board member, Sònia Urpí Garcia, was infected with Pegasus on June 22, 2020, just over a week after being elected to the role on June 13, 2020.

Target: Òmnium Cultural

Multiple individuals around Òmnium were similarly targeted with Pegaus. These included the journalist Meritxell Bonet, who is the spouse of Òmnium’s former president Jordi Cuixart. Bonet was targeted while Cuixart was facing charges for his role in the 2017 referendum, and infected on June 4, 2019, not long before he was to make his final statements at trial. He was later sentenced in October 2019, and pardoned in 2021.

Journalist and historian Marcel Mauri became vice president of Òmnium after Cuixart was sentenced on October 14, 2019. Within ten days of assuming the role, on October 24, 2019, we found evidence of what would be the first of three Pegasus infections of his phone. We also found evidence of extensive Pegasus SMS targeting straddling that period, beginning in February 2018 and ending in May 2020.

Elena Jiménez, another executive board member and the international representative of Òmnium, was also infected with Pegasus. Although we are unable to determine the date of the infection, the case is interesting: her role included dialogue with NGOs throughout Europe including Amnesty International and Frontline Defenders. The compromise of her communications would have likely provided a unique view into Catalan advocacy efforts.

Jordi Bosch, also an executive board member, was infected with Pegasus on or around July 11, 2020.

Catalan’s Open-Source and Digital Voting Community

Joan Matamala runs a bookstore and foundation promoting the Catalan language and culture, originally founded by his father in defiance of Franco’s dictatorship. Matamala also recently founded the Nord Foundation which promotes open-source citizen participation software. Forensic examination of his phone indicates that he was also infected at least 16 times with Pegasus between August 2019 and July 2020.

Matamala was also infected with Candiru spyware. Other members of the Catalan open-source community who work on voting software and decentralization were similarly targeted with Candiru. Their cases are described below in greater detail (See Finding: Catalans Targeted with Candiru).

Lawyers Representing Prominent Catalans

Multiple lawyers representing prominent Catalans were targeted and infected with Pegasus, some extensively. While not all have consented to be named, the targeting suggests that this group was a specific focus for monitoring.

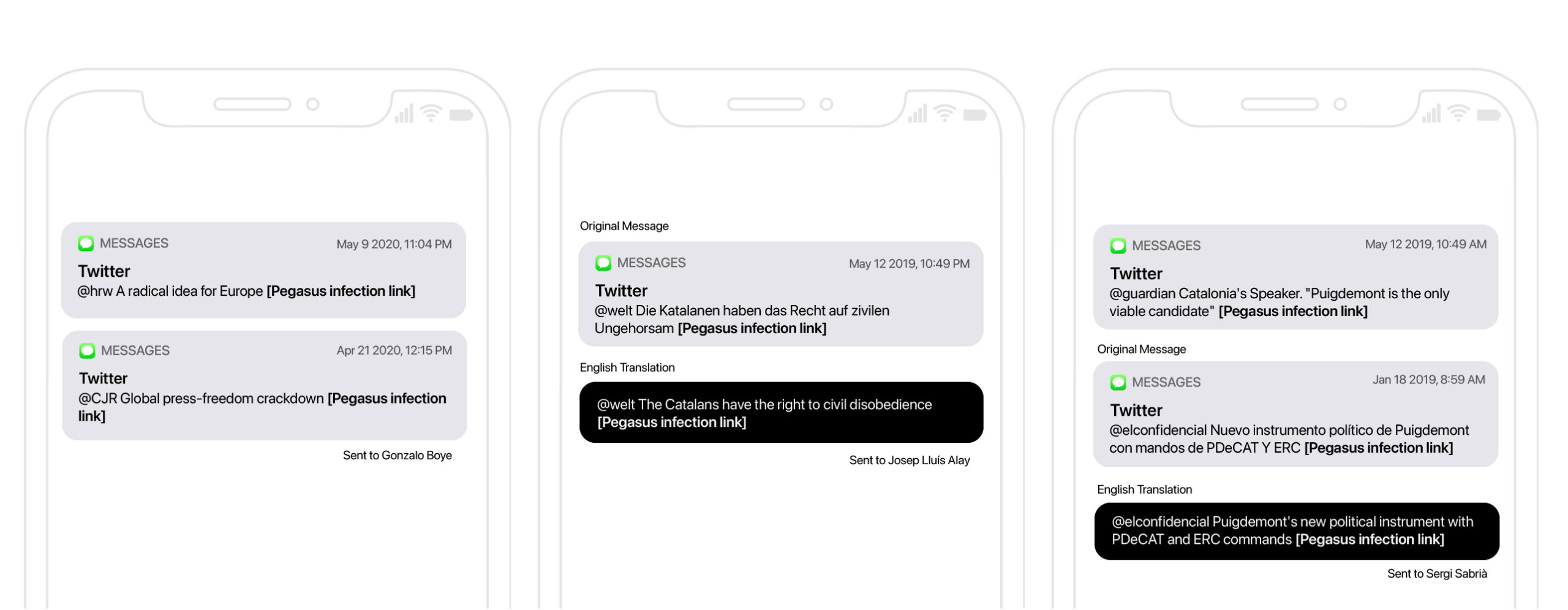

For example, well-known lawyer Gonzalo Boye, who represents Puigdemont (among others), was targeted at least 18 times with infection attempts between January and May 2020. Some of the messages masqueraded as tweets from organisations like Human Rights Watch, The Guardian, Columbia Journalism Review, and Politico.

Boye was successfully infected with Pegasus on or around October 30, 2020. The timing is interesting: one of his clients had been arrested just 48 hours before the infection.

Andreu Van den Eynde, lawyer for prominent Catalans Oriol Junqueras, Roger Torrent, Raül Romeva, and Ernest Maragall, was infected on June 14, 2020. Jaume Alonso-Cuevillas, a lawyer who also represented Puigdemont, was infected with Pegasus, although we were unable to determine the date of the infection. Alonso-Cuevillas is currently a member of the Parliament of Catalonia, former dean of the Barcelona Bar Association, and former President of the European Bar Federation.

Target: Catalan Government, Parliament, and Politicians

Catalan politicians were extensively infected with Pegasus. The targeting took place throughout sensitive negotiations between the Catalan and Spanish governments. This section lists a selection of the cases.

Every Catalan president since 2010 has been targeted or infected with Pegasus, either while serving their term, before, or after their retirement.

President Pere Aragonès (infected while serving as VP during Torra’s Presidency)

- Date Served: 2021-present

- Infected (Pegasus)

Former President Joaquim Torra (infected while in office)

- Date Served: 2018-2020

- Infected (Pegasus)

Former President Carles Puigdemont

- Date Served: 2016 to 2017

- Relational targeting

Former President Artur Mas (infected after leaving office)

- Date Served: 2010-2015

- Infected (Pegasus)

In addition, the leadership and members of Catalan legislative bodies were extensively infected, including multiple presidents of the Catalan parliament either while in office or prior to taking office.

Roger Torrent Former President of the Parliament of Catalonia (targeted while in office)

- Targeted (Pegasus)

Laura Borràs (current President of Catalan parliament, targeted while a member of the Spanish Congress)

- Targeted (Pegasus)

The targeting and infections were expansive and touched a wide range of legislators from at least five Catalan political parties.

Together for Catalonia (Junts per Catalunya)

- 11 Members targeted

Republican Left of Catalonia (Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya)

- 12 Members

Popular Unity Candidacy (Candidatura d’Unitat Popular)

- 4 members

Catalan European Democratic Party (Partit Demòcrata Europeu Català)

- 3 members

Catalan Nationalist Party (Partit Nacionalista Català)

- 1 Member

Taken together, the targeting indicates an extremely well-informed and widespread effort to monitor Catalan political processes. Examination of the SMS targeting also points to a detailed understanding of the targets, their interests, concerns, and activities. The timing of the targeting often directly coincided with specific non-public and sensitive activities such as strategy meetings and negotiations. This is highly suggestive of a well resourced intelligence service.

Exploit Techniques

Victims were infected through at least two vectors: zero-click exploits and malicious SMSes. While users can be trained to be vigilant about not clicking suspicious links, the use of zero-click exploits is especially difficult to defend against as there is no action that a regular user can take that will reliably protect them against this kind of attack.

Zero-Click Exploits

We saw evidence that multiple zero-click iMessage exploits were used to hack Catalan targets’ iPhones with Pegasus between 2017 and 2020.

Discovering Homage

We have identified signs of a zero-click exploit that has not been previously described, which we call HOMAGE. The HOMAGE exploit appears to have been in use during the last months of 2019, and involved an iMessage zero-click component that launched a WebKit instance in the com.apple.mediastream.mstreamd process, following a com.apple.private.alloy.photostream lookup for a Pegasus email address. The WebKit instance in the com.apple.mediastream.mstreamd process fetched JavaScript scaffolding that we recovered from an infected phone. The scaffolding was fetched from /[uniqueid]/stadium/goblin. After performing tests, the scaffolding then fetches the WebKit exploit from /[uniqueid]/stadium/eutopia if tests succeed.

One test run by the scaffolding checks the exact screen resolution in pixels, and compares it with hardcoded values for each type of iPhone hardware, with or without display zoom enabled. If there are multiple possible matches (for example, the iPhone X and Xs share the same screen resolution if the latter is running in “display zoom” mode), then a timing side-channel is tested, which involves measuring the time taken to encrypt a buffer of 2^28 bytes using AES in CBC mode. If the measured time is less than 560ms, then the test concludes that the iPhone device uses PAC (iPhone Xs and above). If the time taken is greater than 560ms, then the test concludes that the device does not use PAC (iPhone X and earlier).

The exploit was fired at the phone on at least the following dates:

Wed, 18 Dec 2019 10:45:03 GMT

Thu, 19 Dec 2019 11:38:45 GMT

Thu, 26 Dec 2019 08:32:51 GMT

Sun, 29 Dec 2019 10:58:04 GMT

Thu, 02 Jan 2020 13:32:49 GMT

Sat, 04 Jan 2020 10:47:05 GMT

Wed, 08 Jan 2020 07:27:46 GMT

Among Catalan targets, we did not see any instances of the HOMAGE exploit used against a device running a version of iOS greater than 13.1.3. It is possible that the exploit was fixed in iOS 13.2. We are not aware of any zero-day, zero-click exploits deployed against Catalan targets following iOS 13.1.3 and before iOS 13.5.1.

The Citizen Lab has reported the exploit to Apple and provided them with relevant forensic artifacts. At this time, we do not have evidence to suggest that Apple device users on up-to-date versions of iOS are at risk.

Kismet

The zero-clicks used also included the KISMET exploit, which was a zero-day in the summer of 2020 against iOS 13.5.1 and iOS 13.7. Though the exploit was never captured and documented, it was apparently fixed by changes introduced into iOS14, including the BlastDoor framework.

The most recent case we have documented of an iPhone belonging to a Catalan target that was infected with Pegasus was in December 2020, via the KISMET exploit.

The 2019 WhatsApp Attack

Citizen Lab has previously confirmed that multiple Catalans were among those targeted with Pegasus through the 2019 WhatsApp attack, which relied on the (now patched) CVE-2019-3568 vulnerability.

SMS-Based Targeting

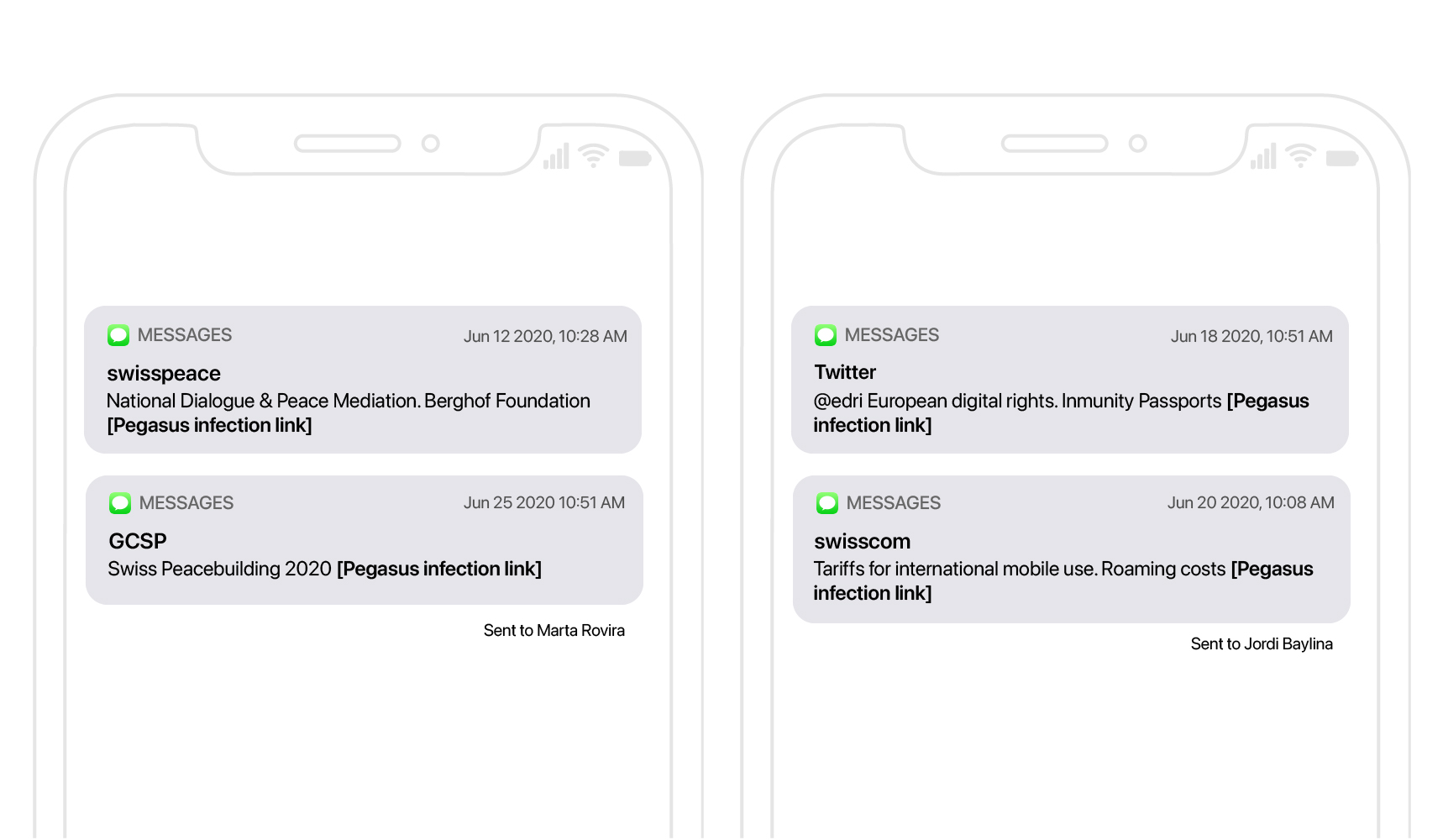

Many victims were targeted using SMS based attacks, and we have collected more than 200 such messages. These attacks involved operators sending text messages containing malicious links designed to trick targets into clicking. In this approach, once a victim clicks on a link, the device is infected via a Pegasus exploit server.

Sophistication and personalization of the messages varied across attempts, but they reflect an often detailed understanding of the target’s habits, interests, activities, and concerns. In many cases, either the timing or the contents of the text were highly customised to the targets and indicated the likely use of other forms of surveillance.

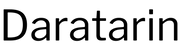

Jordi Baylina is the technology lead at Polygon, a popular decentralised Ethereum scaling platform. He is also an advisor on projects related to digital voting and decentralisation, and

has built a widely-used privacy toolkit. He was extensively targeted with Pegasus, receiving at least 26 infection attempts. Ultimately, he was infected at least eight times between October 2019 and July 2020.

Baylina received a text message masquerading as a boarding pass link for a Swiss International Air Lines flight he had purchased. Targeting in this case indicates that the Pegasus operator may have had access to Baylina’s Passenger Name Record (PNR) or other information collected from the carrier.

Fake Mobile Boarding Pass

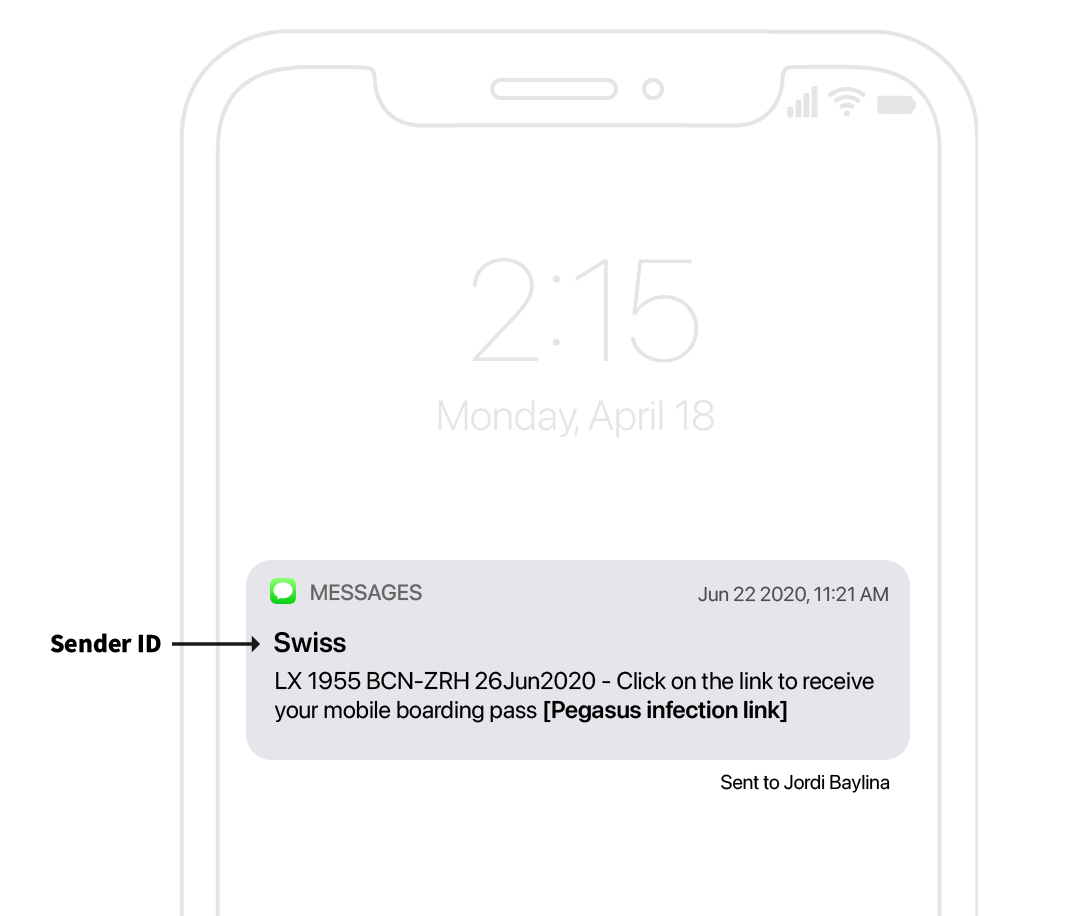

Another common mode of targeting was to masquerade as official notifications from Spanish government entities, including the Tax and Social Security authorities.The messages also used SMS Sender IDs to masquerade as official agency accounts.

Notably, fake official messages were sometimes highly personalized. For example, a message sent to Jordi Baylina included a portion of his actual official tax identification number, suggesting that the Pegasus operator had access to this information.

Fake Official Notifications

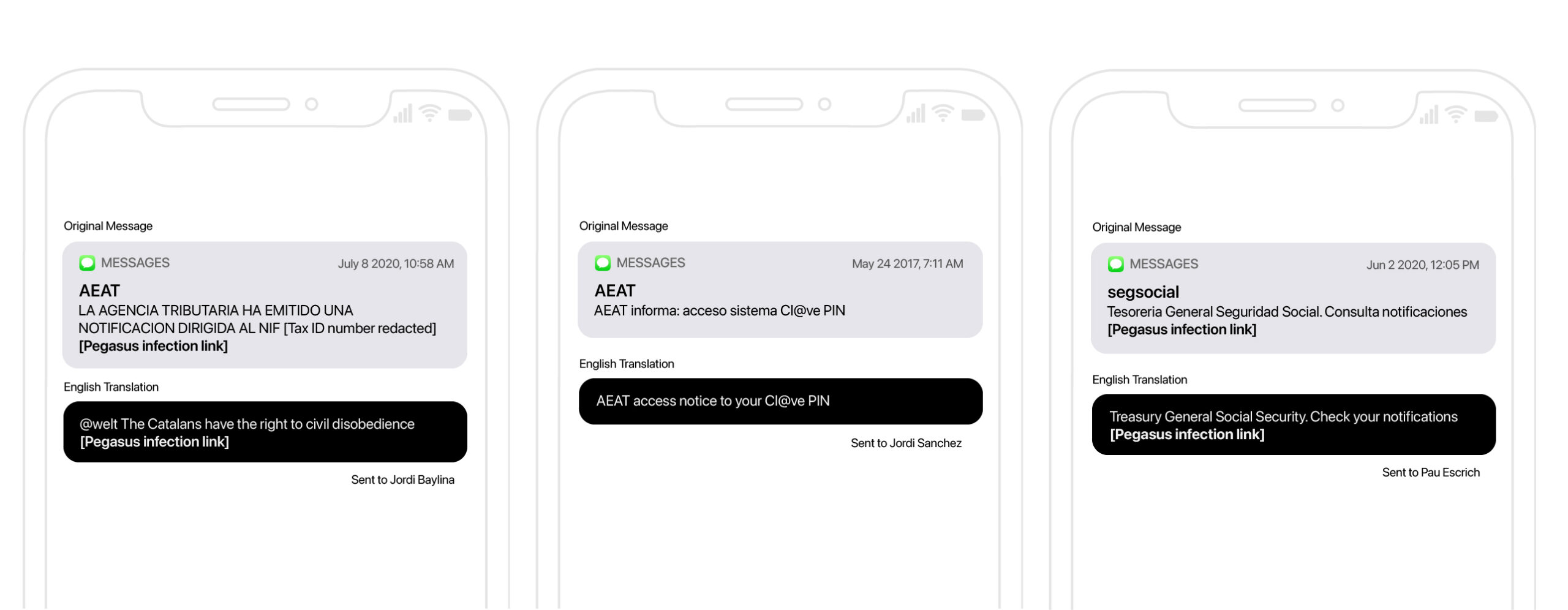

We also observed regular use of package tracking or delivery notifications. Some were personalised, containing the targets’ names.

Fake Package Notification

Many messages masqueraded as Twitter or news updates, typically focused on topics of interest to the target. News organizations impersonated included international outlets such as The Guardian, Financial Times, and Die Welt, English language media like the Columbia Journalism Review, as well as regional media like La Vanguardia, Europa Press, El Temps, El Confidencial, and so on.

Fake Twitter & News Updates

Cross-Border SMS Targeting

Catalans were also targeted outside of Catalonia with Pegasus infection attempts, including SMS messages sent to numbers with non-Spanish country codes. For example, Marta Rovira was targeted while in Switzerland on her Swiss telephone number. Both SMS messages used an SMS Sender ID impersonating Swiss entities: Swisspeace is an NGO, and the Geneva Center for Security Policy is a foundation established and primarily funded by the Swiss government.

Jordi Baylina was also targeted with infection attempts masquerading as a tweet from German NGO European Digital Rights and a tweet purporting to be the Swiss telecom provider Swisscom.

The text messages pointed to a cluster of domains pointing to infrastructure previously identified through the Citizen Lab’s Internet scanning and fingerprinting as belonging to NSO Group’s Pegasus infection infrastructure.

Finding: Catalans Targeted with Candiru

In July 2021, we published “Hooking Candiru,” in which we identified and analysed Candiru’s mercenary spyware, in cooperation with Microsoft. At the time we did not name the “patient zero” for our analysis. He is Joan Matamala. As noted above, Matamala was extensively targeted and infected with Pegasus.

While conducting a preliminary investigation into Candiru spyware we identified evidence of a live Candiru infection on an institutional network backbone used by a consortium of Catalan universities.

With the help of technicians from the relevant institutions, the infection was localized to a campus of the University of Girona. Further investigation confirmed that Matamala was the owner of the infected device, and that an infection was live.

Using a pretext, Matamala’s colleagues asked him to step away from the computer and into the hallway. Once the situation had been explained, he consented to a forensic analysis of the device.

We were able to successfully forensically extract the malicious spyware and determine that it was persistently installed on his device.

With Matamala’s consent, we shared forensic traces of the spyware with Microsoft’s Threat Intelligence Center (MSTIC), who discovered over 100 victims across ten countries. Microsoft describes the victims of Candiru (which they refer to as SOURGUM) as including “politicians, human rights activists, journalists, academics, embassy workers, and political dissidents.”

Microsoft also discovered two zero-day vulnerabilities (CVE-2021-33771, CVE-2021-33771) employed by Candiru to infect Windows systems, and patched them in July 2021.

Identifying Additional Candiru Targets

Forensic evidence pertaining to Candiru was obtained from victims who consented to participate in a research study with the Citizen Lab. Victims publicly named in the report consented to being identified as such.

| Case Type | Number observed |

|---|---|

| Forensically Confirmed Candiru Infection | 1 |

| Confirmed Candiru Targeting | 3 |

| Total Cases | 4 |

Table 3: Case Overview for Pegasus Infections & Targeting

Our continuing investigation into Candiru in connection with Catalonia revealed at least three other individuals were targeted with Candiru spyware via email messages: Elies Campo,1 Xavier Vives, and Pau Escrich. Escrich was also targeted with a Pegasus infection attempt on June 2, 2020. Escrich and Vives are co-founders of Vocdoni, a censorship-resistant secure digital voting protocol that Òmnium used during its internal elections. Elies Campo, along with Jordi Baylina, both served as advisors to Vocdoni.

Candiru Email Targeting

We identified a total of seven emails containing the Candiru spyware, via links to the domain name stat[.]email.

The email messages were well constructed efforts to entice the targets to click on the links. For example, two of the three targets (Xavier Vives and Pau Escrich) received an email in Figure 6 in early February 2020, featuring the official emblem of the Government of Spain, and reporting that the World Health Organization had declared COVID-19 to be a “Public Health Emergency of International Importance” in January.

The email contained a link to recommendations for what to do in cases of infection with COVID-19. Clicking on the link would have infected the targets’ computers with Candiru’s spyware.

One of the targets, Pau Escrich, received an email impersonating the Mobile World Congress (MWC), with a link to tickets. Had he clicked on the link, his computer would have been infected with Candiru’s spyware. The email content appears to be copied from a legitimate Mobile World Congress email sent to news105@tutanota[.]com, which may be an email address used by the spyware operators.

Interestingly, Elies Campo was targeted with a well-crafted message purporting to be from Barcelona’s Mercantile Registry (Figure 7). The message contained factual information about a company that he administered and purported to be a warning that a similarly-named company was registered in Panama. Such a message indicates a high degree of awareness of Campo’s activities, and would be likely to generate a click. The message was received while Campo was in the US.

The Mobile World Congress email containing a Candiru link is also noteworthy, as it echoes bait content in a Pegasus SMS sent to a separate target, Jordi Baylina:

This content similarity hints at a potential overlap of knowledge and targeting themes between the Candiru and Pegasus operators.

Candiru’s Capabilities

Our analysis of Candiru’s spyware showed that Candiru was designed for extensive access to the victim device, such as extracting files and browser content, but also stealing messages saved in the encrypted Signal Messenger Desktop app. Figure 9 shows an excerpt of Windows spyware functionality described in a leaked Candiru contract.

Microsoft’s analysis established that Candiru’s spyware, which they call Devil’s Tongue, also had functionality allowing the operator to directly use a victim’s cloud accounts on their infected device to send or post messages using their accounts. While it can be used as part of infection targeting, the same functionality could be used to plant evidence that would frame an individual in a way that would be exceedingly difficult for the victim to refute.

Attribution to NSO’s Pegasus

The Citizen Lab regularly conducts large-scale scanning, fingerprinting, and monitoring for evidence of Pegasus infections. We observed the following Pegasus domain names used in SMS infection attempts sent to Catalan targets:

| Version of Pegasus Infrastructure | Domains |

|---|---|

| Version 1 | nnews[.]co |

| Version 3 |

statsads[.]co

|

| Version 4 |

redirstats[.]com

|

| Version 4.5 | 123tramites[.]com |

Table 4: CatalanGate Pegasus Infrastructure Domains & Versions

Of these domains, only nnews[.]co and 123tramites[.]com were complete matches for our fingerprint, and statsads[.]co was a partial fingerprint match. Some of the domains appear to have customised behaviour or setup, perhaps in order to make them less visible to our Internet scanning. For example, our Athena method for determining which domain names were operated by a single customer (applicable to Version 3 domains) did not work on statsads[.]co or adsmetrics[.]co. Additionally, our Version 3 fingerprint was only a partial match for statsads[.]co (the discrepancy was that the server exhibited 300ms of additional latency, perhaps because the operator fronted their NSO Group-supplied infrastructure with their own custom server). Our Version 3 fingerprint did not match adsmetrics[.]co at all, perhaps again because of a separate custom server that the operator used to front their NSO-supplied infrastructure. We also did not detect any of the Version 4 domains, as they used SSL certificates issued by cPanel; we only scanned for SSL certificates from specific issuers, of which cPanel was not one.

Despite the apparent customizations, we have developed evidence that all of the domains are linked to NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware.

| Domain | Evidence of link to Pegasus |

|---|---|

nnews[.]co |

Matched our “Version 1” fingerprint |

statsads[.]co |

Partially matched our “Version 3” fingerprint. Pegasus forensic indicators on device shortly after SMS containing link was read (and presumably clicked on) |

adsmetrics[.]co |

Similar bait content (message from “twitter” posing as tweet from “@ScotNational”) as message containing link to statsupplier[.]com

|

redirstats[.]com |

Certain setup characteristics match statsupplier[.]com: nameserver hosted on kualo.net, and SSL certificate from cPanel |

statsupplier[.]com |

Pegasus forensic indicators on device shortly after SMS containing link was read (and presumably clicked on) |

infoquiz[.]net |

Certain setup characteristics match statsupplier[.]com: nameserver hosted on kualo.net, and SSL certificate from cPanel |

123tramites[.]com |

Matched our “Version 4.5” fingerprint |

Table 5: CatalanGate Domains, Attribution to Pegasus

Most Domains Appear to be Operated by a Single Customer

We link each domain (except nnews[.]co) to a single Pegasus customer. We link the domain names infoquiz[.]net, statsupplier[.]com and redirstats[.]com to a single customer, because they shared setup characteristics (nameserver hosted on kualo.net and SSL certificate from cPanel). We further believe that 123tramites[.]com was operated by the same customer, because an SMS with a link to 123tramites[.]com used identical bait content to an SMS with a link to statsupplier[.]com.

We further believe that adsmetrics[.]co represents the same customer, as we saw similar bait content (message from “twitter” posing as tweet from “@ScotNational”) in an SMS with a link to statsupplier[.]com. We further believe that statsads[.]co represents the same customer, as we saw similar bait content (message from “twitter” posing as tweet from “@elconfidencial”) in an SMS with a link to statsupplier[.]com. We are unsure if nnews[.]co represents the same customer, although we suspect that even if the customer is separate, it is at least a related customer: we did locate one individual who received Pegasus links from: nnews[.]co, statsads[.]co and statsupplier[.]com.

Attribution to Candiru

In our July 2021 Hooking Candiru report, we listed 764 domain names that we linked to Candiru. Our initial ground truth was a self-signed TLS certificate mentioning an email address on the domain name candirusecurity[.]com, which is registered to Candiru.

Three of the domain names in our list of 764, adtrack[.]link, cortana[.]cloud, and rbtlnk[.]net were interesting, because they initially matched our Candiru fingerprint CF1, but around April 2018, began to exhibit an unusual behaviour that we believe represents customization employed by the Candiru customer using these domain names. Starting from around May 2018, any HTTPS traffic on port 443 to these three domain names was routed to a Tor client running on the server (identifiable by the distinctive TLS certificates it returned), but only if the SNI was set to adtrack[.]link, cortana[.]cloud, rbtlnk[.]net, or any other domain name configured on the server. The Tor behaviour simply appeared to be a “decoy” behaviour designed to confuse or mislead researchers who happened upon these domain names or their IP address. The spyware did not appear to use Tor for data exfiltration, nor was the IP, 185.181.8[.]155, used as a relay by legitimate Tor users. Because this “Tor behaviour” was different from the behaviour of other customers’ Candiru servers around this time, we hypothesised that the Candiru customer in question was attempting to “customise” their servers, perhaps in order to make them less visible to our Internet scanning. We scanned the Internet for other IPs exhibiting this same “Tor behaviour,” and found only one, 185.193.38[.]113, which was pointed to by a single domain name at the time, stat[.]email.

We attributed stat[.]email not only to Candiru, but also to the same Candiru customer that was using the other “Tor behaviour” domain names. Indeed, we located a Catalan target (Matamala) whose computer was communicating with domain names pointing to 185.181.8[.]155, and recovered a sample of Candiru’s spyware from his computer. Additionally, all of the Candiru emails sent to Catalan targets used the domain stat[.]email.

Attribution to a Government

At this time the Citizen Lab is not conclusively attributing these hacking operations to a particular government, however a range of circumstantial evidence points to a strong nexus with one or more entities within Spanish government, including:

- The targets were of obvious interest to the Spanish government;

- The specific timing of the targeting matches events of specific interest to the Spanish government;

- The use of bait content in SMSes suggests access to targets personal information, such as Spanish governmental ID numbers; and,

- Spain’s CNI has reportedly been an NSO Group Customer, and Spain’s Ministry of Interior reportedly possesses an unnamed but similar capability.

We also judge it unlikely that a non-Spanish Pegasus customer would undertake such extensive targeting within Spain, using SMSes, and often impersonating Spanish authorities. Such a multi-year clandestine operation, especially against high profile individuals, has a high risk of official discovery, and would surely lead to serious diplomatic and legal repercussions for a non-Spanish government entity.

Independent Validation

A selection of four Pegasus victims provided forensic artefacts from their devices to technical experts with Amnesty International’s Security Lab, which independently examined them for evidence of Pegasus infections and targeting.

- Elisenda Paluzie and Sònia Urpí Garcia of ANC

- Journalist Meritxell Bonet

- Politician & professor Jordi Sànchez

In each case, Amnesty’s Security Lab independently confirmed our findings that these individuals were infected, using their own forensic methodology. This independently validates the soundness of the forensic methods that the Citizen Lab used in this report to identify Pegasus infections and targeting.

Conclusion

This report details extensive surveillance directed against Catalan civil society and government using mercenary spyware. According to NSO Group, Pegasus is sold exclusively to governments, and finding such an operation inevitably implicates a government. While we do not currently attribute this operation to specific governmental entities, circumstantial evidence suggests a strong nexus with the government of Spain, including the nature of the victims and targets, the timing, and the fact that Spain is reported to be a government client of NSO Group.

Call for an Investigation

The seriousness of the case clearly warrants an official inquiry to determine the responsible party, how the hacking was authorised, what legal framework governed the hacking and what judicial oversight applied, the true scale of the operation, the uses to which the hacked material was put, and how hacked data was handled, including to whom it may have been provided.

Window into a More Extensive Operation?

The list of confirmed victims and targets is striking. Our research has uncovered at least 65 Catalans whose devices were either infected or targeted with spyware. The investigation was labor-intensive, and there are many individuals who have not had their devices checked. Furthermore, our methods have limited insight into Android infections, which represent a large proportion of users in the region. Thus, we suspect that the total number of victims and targets is much higher.

This extraordinarily high number of confirmed mercenary spyware victims and targets in a single case is by far the largest in all of the Citizen Lab’s prior research, including our reports on Al Jazeera (36 victims) and El Salvador (35 victims).

Our investigation gives a window into what is likely a larger effort to place a significant slice of Catalan civil society under targeted surveillance for several years. This effort has resulted in the total surveillance of Catalan politicians in certain categories, such as multiple members of the European Parliament and every Catalan president since 2010.

Unrestrained, Unnecessary, and Disproportionate?

The case is notable because of the unrestrained nature of the hacking activities. The list includes numerous elected officials of Catalonia’s government, as was every Catalan member of the European Parliament that supported independence. Staff members and friends are also among the list. So, too, were numerous members of Catalan civil society, as well as lawyers representing Catalans (raising questions of attorney-client privilege violations).

Egregiously, family members of apparent targets were also targeted and infected. For example, two physicians who use their devices to handle confidential and sensitive patient information were likely infected because they are the parents of the true target. Indeed, the prominent physician Dr. Elias Campo (the father of Elies Campo) was infected on his official hospital-issued device.

The hacking also extended beyond Spain into other EU countries, including Belgium and Germany, suggesting possible breaches of appropriate conduct for lawful cross-border investigations, or violations of local law. Targeting was also observed in Switzerland, which notably included impersonating Swiss organisations, including a government-supported foundation, raising further questions about the disregard for Swiss law.

This very wide target list raises questions about whether the principles of necessity and proportionality have been fulfilled. Many of the victims were not charged with serious crimes, and most were neither criminals and certainly not terrorists—the typical justifications mercenary surveillance companies employ for sales of their spyware to government clients.

It is also concerning that this surveillance occurred as the Spanish government and Catalan officials were undertaking negotiations around political autonomy. If Spanish authorities are responsible, clandestinely eavesdropping on the opposite side of a negotiation, including in some cases their legal representatives or relatives, is a clear act of bad faith.

Hacking in the EU: Lack of Rules and Judicial Oversight?

If the Spanish government is responsible for this case, it raises urgent questions about whether there is proper oversight over the country’s intelligence and security agencies, as well as whether there is a robust legal framework that authorities are required to follow in undertaking any hacking activities. Formally, the operations of Spain’s security agencies are overseen by the judiciary and the relevant minister. However, it is hard to conceive how a properly functioning oversight mechanism would permit extensive and, in some cases, reckless hacking of numerous elected officials at such a sensitive time. It is also unclear what safeguards were in place, if any, to ensure the protection of any hacked data, and how it was handled.

The hacking of the devices of relatives of principal targets, such as innocent spouses and parents, is especially disturbing. Such extensive clandestine hacking by a state against these types of targets is almost certainly outside of the scope of what would be permissible under international human rights law.

While Europe has recently made great strides around privacy and data protection, such as with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the picture is less bright around the independent oversight of intelligence agencies, which remain largely cloaked in secrecy and may be exempt from rules around privacy applied to other entities. The possibility that an EU member state is responsible for a massive domestic surveillance operation with political overtones should serve as a wake-up call for a collective inquiry into the need for effective oversight.

Finally, the case is also notable because Spain is a democracy, and this case adds to the growing number of other democracies we have discovered that have abused mercenary spyware, including Poland, India, Israel, and El Salvador. While it is true and widely acknowledged now that spyware and commercial surveillance technologies embolden authoritarian regimes and are contributing to the spread of authoritarian practices worldwide, this case is a good reminder that all countries are prone to abusing spyware when safeguards and oversight are absent—even democratic ones, like Spain.

Hacking: A Risky Tool for Criminal Investigations and Prosecutions

The objective behind the hacking we uncovered is unknown at this time. However, the potential application of Pegasus or Candiru spyware to extract information to use in the context of criminal investigations and prosecutions is risky because it may facilitate the use of tainted or planted evidence by state authorities. These risks are particularly prevalent in countries where government hacking is not subject to a rigorous legal framework and effective judicial oversight, and there are few or no requirements for ensuring the integrity of information collected.

Spyware such as Pegasus modifies the operating system and files on an infected device. It is common guidance that once a device has been remotely penetrated and infected, the integrity of data on the device may be tainted and could certainly be challenged in court.

Furthermore, we observed that Candiru spyware has the capability to send messages under the identity of the victim, from their device. Forensically determining that the victim did not send the messages would be extremely difficult. Such a powerful capability could easily be misused to plant evidence. For example, in a recent case in India where incriminating evidence was allegedly planted by hackers on an activist’s device who was then charged with terrorism.

Another Indictment of the Mercenary Spyware Industry

This remarkable combination of high volume and unrestrained abuses points to a serious absence of regulatory constraints, both over sales by the mercenary companies involved and the use of such powerful surveillance tools by the government client or clients. It is now well established that NSO Group, Candiru, other companies like them, as well as their various ownership groups, have utterly failed to put in place even the most basic safeguards against abuse of their spyware. What we find in Spain is yet another indictment of this industry.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the civil society organisations, political groups, and individuals who graciously agreed to share forensic artefacts with this investigation. And everyone who assisted in gathering materials. Without the participation of targeted groups, and their willingness to come forward, this investigation and report would not have been possible.

Special thanks to Sharly Chan, Émilie LaFlèche, Miles Kenyon, Adam Senft, and Mari Zhou for communications, graphics, editing, and research support.

Special thanks to Amnesty International’s Security Lab for the methodological validation.

Special thanks to the Domestic Data Streamers team for graphical work.

Appendix A: Targets

Forensic evidence was obtained from victims who consented to participate in a research study with the Citizen Lab. Further, victims publicly named in this report consented to be identified as such, while other targets chose to remain anonymous.

| Name | Organization(s) | 2019 WhatsApp Pegasus Notification | Pegasus SMSes | Forensically Confirmed Pegasus Infection | Targeted / Infected with Candiru |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alba Bosch | Political activist | – On or around 2020-05-14 | |

| Albano Dante Fachin | Journalist, Former Member of the Parliament of Catalonia |

[Unable to determine specific infection date(s)] | |

| Albert Batet | Member of the Parliament of Catalonia, Junts per Catalunya |

2 | – On or around 2019-10-24 – On or around 2020-07-07 |

| Albert Botran | Member of the Congress of Deputies of Spain, Candidatura d’Unitat Popular |

– On or around 2020-12-01 | |

| Andreu Van den Eynde | Lawyer for Junqueras, Torrent, Romeva, and Maragall | – On or around 2020-05-14 | |

| Anna Gabriel | Former Member of the Parliament of Catalonia Candidatura d’Unitat Popular |

Yes | |

| Anonymous 1 | 1 | – On or around 2020-05-26 | |

| Anonymous 2 | – On or around 2019-12-12 | ||

| Anonymous 3 | [Unable to determine specific infection date(s)] | ||

| Anonymous 4 | – Sometime between 2018-10-04 – 2019-11-05 | ||

| Antoni Comín | Member of European Parliament, Junts per Catalunya |

– Sometime between 2019-08-16 – 2020-01-18 | |

| Arià Bayé | Board Member Assemblea Nacional Catalana | 1 | |

| Arnaldo Otegi | General Secretary, Euskal Herria Bildu | [Unable to determine specific infection date(s)] | |

| Artur Mas | President of Catalonia (2010-2015) | [Unable to determine specific infection date(s)] | |

| Carles Riera | Member of the Parliament of Catalonia, Candidatura d’Unitat Popular |

4 | – Sometime before 2019-06-11 |

| David Bonvehi | President Partit Demòcrata Europeu Català Former Member of the Parliament of Catalonia |

32 | – Sometime between 2018-09-30 – 2019-01-30 – On or around 2019-02-15 – On or around 2019-04-05 – On or around 2019-04-09 – Sometime between 2020-02-08 – 2020-06-16 |

| David Fernández | Former Member of the Parliament of Catalonia, Candidatura d’Unitat Popular |

1 | |

| David Madi | Businessman Former advisor to President Artur Mas |

[Unable to determine specific infection date(s)] | |

| Diana Riba | Member of European Parliament, Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya |

– On or around 2019-10-28 | |

| Dolors Mas | Businesswoman, event organizer. | – Sometime between 2018-09-27 – 2019-08-28 – On or around 2019-08-28 |

|

| Dr. Elias Campo | Senior Consultant, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Member, U.S. National Academy of Medicine Director, August Pi i Sunyer Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBAPS) |

– On or around 2019-12-18 | |

| Elena Jimenez | International Advocacy and member of Legal team, Òmnium Cultural |

[Unable to determine specific infection date(s)] | |

| Elies Campo | Former Growth, Business Development and Partnerships, Telegram Messenger | Targeted | |

| Elisenda Paluzie | President Assemblea Nacional Catalana Professor of Economics at the University of Barcelona |

4 | – On or around 2019-10-29 |

| Elsa Artadi | Former Minister of Presidency of Catalonia, Junts per Catalunya |

1 | |

| Ernest Maragall | Member of the Parliament of Catalonia, Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya. |

Yes | |

| Ferran Bel | Member of the Congress of Deputies of Spain, Partit Demòcrata Europeu Català |

2 | |

| Gonzalo Boye | Lawyer for President Puigdemont, President Torra and MEP Antoni Comín. | 18 | – On or around 2020-10-30 |

| Jaume Alonso Cuevillas | Lawyer representing multiple prominent Catalans Member, Parliament of Catalonia, Former Member of the Congress of Deputies of Spain. |

[Unable to determine specific infection date(s)] | |

| Joan Matamala | Businessman, President of the Fundació Llibreria Les Voltes. |

– On or around 2019-08-07 – On or around 2019-11-18 – On or around 2019-11-20 – On or around 2019-11-26 – On or around 2020-02-18 – On or around 2020-03-02 – On or around 2020-04-11 – On or around 2020-04-14 – On or around 2020-05-06 – On or around 2020-05-25 – On or around 2020-06-05 – On or around 2020-06-17 – On or around 2020-06-23 – On or around 2020-07-02 – On or around 2020-07-09 – On or around 2020-07-13 |

Infected |

| Joan Ramon Casals | Former Director, Office of President Torra Former Member of the Parliament of Catalonia, Junts per Catalunya |

[Unable to determine specific infection date(s)] | |

| Joaquim Jubert | Member of the Parliament of Catalonia, Junts per Catalunya |

– On or around 2019-10-28 | |

| Joaquim Torra | President of Catalonia (2018-2020) | 8 | – On or around 2020-04-21 – On or around 2020-05-19 – On or around 2020-06-11 – On or around 2020-06-21 – On or around 2020-07-07 – On or around 2020-07-09 – On or around 2020-07-13 – On or around 2020-07-15 |

| Jon Iñarritu | Member of the Congress of Deputies of Spain, Euskal Herria Bildu | – On or around 2020-12-02 | |

| Jordi Baylina | Open-source Developer, Technology lead at Polygon | 26 | – On or around 2019-10-29 – On or around 2019-11-15 – On or around 2019-11-26 – On or around 2019-11-26 – On or around 2019-12-11 – On or around 2019-12-23 – On or around 2020-06-19 – On or around 2020-07-11 |

| Jordi Bosch | Former Board member, Òmnium Cultural | – On or around 2020-07-11 | |

| Jordi Domingo | Member, Assemblea Nacional Catalana | Yes | |

| Jordi Sanchez | Former President Assemblea Nacional Catalana | 25 | – On or around 2017-05-26 – On or around 2017-09-11 – On or around 2017-09-15 – On or around 2017-10-13 |

| Jordi Solé | Member of European Parlament Former Member of the Parliament of Catalonia Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya |

1 | – On or around 2020-06-11 – On or around 2020-06-27 |

| Josep Costa | Lawyer, Former Vice President of the Catalan Parliament Former Member of the Parliament of Catalonia |

4 | – On or around 2019-07-15 – On or around 2019-12-17 – On or around 2019-12-21 – On or around 2019-12-30 |

| Josep Lluís Alay | Office Director, President Puigdemont Professor of Asian History, University of Barcelona |

6 | – On or around 2020-07-13 |

| Josep Ma Ganyet | Businessman Professor, Pompeu Fabra University |

1 | – On or around 2019-10-23 – On or around 2020-01-08 – On or around 2020-03-02 |

| Josep Maria Jové | Member of the Parliament of Catalonia, Former General Secretary of the Vice-Presidency of Economy and Finance, Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya |

1 | [Unable to determine specific infection date(s)] |

| Josep Rius | Vice President at Junts per Catalunya Former Puigdemont’s Office Director |

– Sometime between 2019-07-23 – 2019-10-10 | |

| Laura Borràs | President of the Parliament of Catalonia, Former Member of the Congress of Deputies of Spain, Junts per Catalunya |

1 | |

| Marc Solsona | Former Member of the Parliament of Catalonia, Partit Demòcrata Europeu Català |

[Unknown infection date(s)] | |

| Marcel Mauri | Former Vice President, Òmnium Cultural | 19 | – On or around 2019-10-24 – On or around 2020-02-25 – On or around 2020-05-06 |

| Marcela Topor | Journalist | 4 | – On or around 2019-10-07 – On or around 2020-01-04 |

| Maria Cinta Cid | Senior Consultant, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona Professor, University of Barcelona Senior Group Leader, IDIBAPS |

– On or around 2019-12-17 – On or around 2019-12-19 – On or around 2019-12-23 – On or around 2019-12-28 – On or around 2019-12-30 – On or around 2020-01-03 – On or around 2020-01-05 – On or around 2020-01-09 |

|

| Marta Pascal | “General Secretary, Partit Nacionalista de Catalunya Former Member of the Congress of Deputies of Spain” |

2 | |

| Marta Rovira | General Secretary, Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya Former Member of the Parliament of Catalonia |

2 | – On or around 2020-06-12 – On or around 2020-07-13 |

| Meritxell Bonet | Journalist | – On or around 2019-06-04 | |

| Meritxell Budo | Former Minister of the Presidency of Catalonia Junts per Catalunya |

8 | [Unable to determine specific infection date(s)] |

| Meritxell Serret | Member of the Parliament of Catalonia, Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya |

[Unable to determine specific infection date(s)] | |

| Miriam Nogueras | Member of the Congress of Deputies of Spain Junts per Catalunya |

[Unable to determine specific infection date(s)] | |

| Oriol Sagrera | General Secretary of the Ministry of Business and Labor, Former Head of the Cabinet of the Presidency of the Parliament of Catalonia. Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya |

3 | – On or around 2019-03-22 – On or around 2019-04-02 – Sometime between 2019-04-06 – 2019-10-06 – On or around 2020-07-08 |

| Pau Escrich | Open-source Developer, CTO Aragon Labs | 1 | Targeted |

| Pere Aragonès | President of Catalonia | 3 | [Unable to determine specific infection date(s)] |

| Pol Cruz | European Parliament Assistant | – On or around 2020-07-07 | |

| Roger Torrent | Minister of Business and Labour of Catalonia, Former President of the Parliament of Catalonia, Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya |

Yes | 1 |

| Sergi Miquel | General Manager Council for the Republic of Catalonia | Yes | |

| Sergi Sabrià | Former Member of the Parliament of Catalonia, Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya |

17 | – On or around 2020-04-11 – On or around 2020-05-05 – On or around 2020-05-10 – On or around 2020-05-13 – On or around 2020-07-13 |

| Sònia Urpí | Board Member, Assemblea Nacional Catalana | 2 | – On or around 2020-06-22 |

| Xavier Vendrell | Former Member of the Parliament of Catalonia, Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya |

– On or around 2019-11-04 – On or around 2020-04-14 |

|

| Xavier Vives | Co-founder Vocdoni Open-source Developer |

Targeted |

[ comments ]